In the early 1970’s, environmental concern was quickly rising. Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring (which I wrote about here), alerted millions to the dangers of pesticides and pointed out that decisions based on partial knowledge and expediency could have collateral consequences worse than the problems being addressed.

Images from left: Cuyahoga River in flames due to oily waste and debris; middle: The George Washington Bridge in Heavy Smog, 1973, Chester Higgins; right: Santa Barbara Oil Spill, 1969

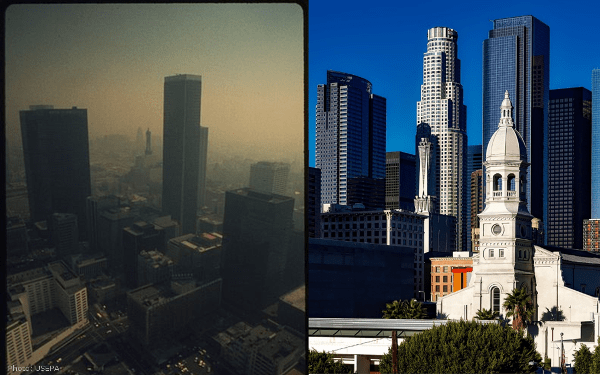

In addition, a devastating oil spill coated the water and coastline near Santa Barbara, California; an oil-slicked river in Ohio (the Cuyahoga) habitually burst into flames; smog enveloped cities (with at least two smog episodes in New York killing over 200 people each), hazardous lead levels were discovered in Central Park; omnipresent litter stacked up along America's roadways. All this precipitated a skyrocketing public concern. Between 1965 and 1970, the percentage of Americans believing that pollution was a serious problem rose from one-third to 70%.

In late 1970, this rising concern led a reluctant President Richard Nixon to take action. Rather than ceding the popular issue to a political opponent, Nixon chose to address these rising concerns, and the EPA was created.

Nixon presented Congress with a 37-point message on the environment and the Council of Environmental Quality was established (still intact, but currently leaderless) as part of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), with the purpose to consider how to organize federal government programs designed to reduce pollution.

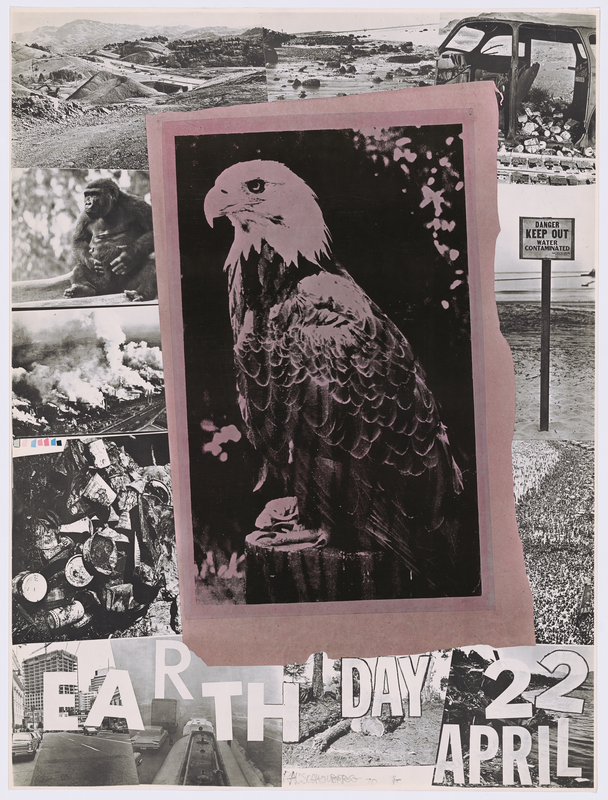

Momentum continued to grow throughout 1970, with the first Earth Day on April 22nd drawing 20 million people (or 10% of the U.S. population at the time). After hearings in the Senate and House, the Environmental Protection Agency was established in December of 1970 to consolidate the enforcement of regulation in the areas of water pollution, air pollution, solid waste management, parklands and public recreation, and organizing for action.

Formerly, these responsibilities lay largely with the states, a system that had proved ineffective in fighting threats against the environment. The state-run system failed because the ability to do research and share knowledge was severely limited, state-by-state regulations created artificial borders of regulations which environmental impacts didn't stay within, and varying regulations led to unethical corporations shopping around to find the state with the least oversight—not a formula for decision-making that prioritized a healthy environment. The current idea of turning environmental control over to the states isn't new—it would actually be returning to the broken system that the EPA was created to replace.

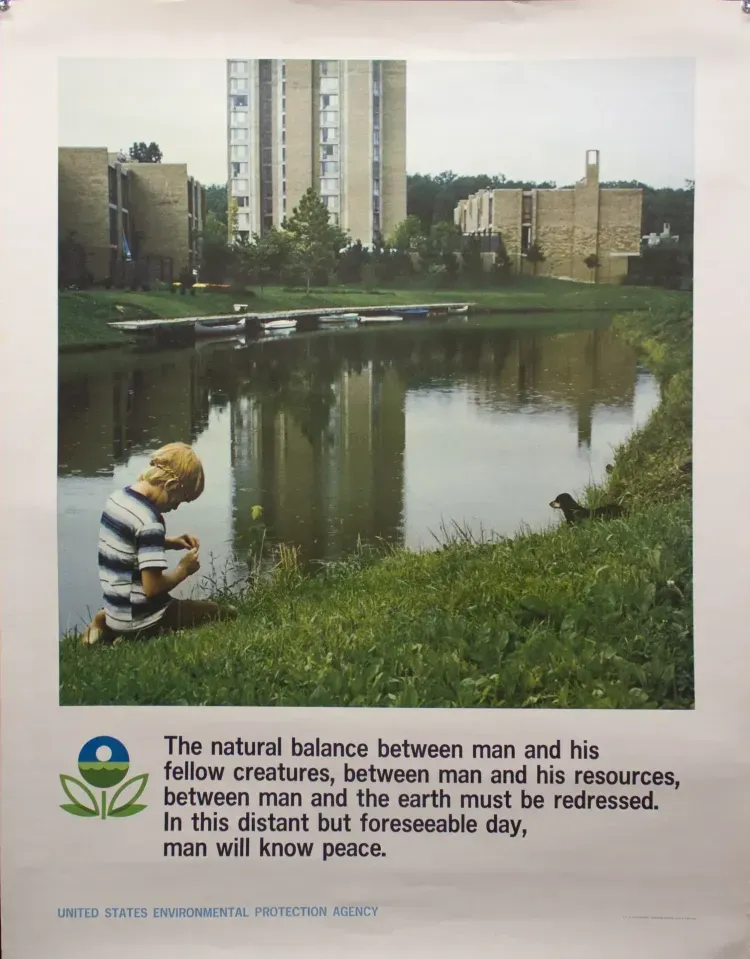

One of the things the first director of the EPA, William Ruckelshaus, recognized was the importance of having public sentiment backing up the agency. Navigating between business interests and environmental concerns would be difficult; illuminating the needs so that the public would continue to support and drive the movement would be crucial to maintaining the strength of the agency.

Thus, in November 1971, the newly created Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced a huge photodocumentary project to record changes in the American environment. Documerica employed 100 photographers to document the U.S.'s rapidly decaying natural environment. More than 80,000 images were submitted, 20,000 of which were included in the final collection. A few of these are featured below. The remaining can be found here.

Images: Hollywood freeway, May 1972, Gene Daniels; Hillside dump, May 1972, Gene Daniels; Abandoned car in Jamaica Bay, 1973, Arthur Tress; Trash and Tires in Baltimore Harbor, Jim Pickerell, 1973; Scum along shore, May 1972, Belinda Rain; Smog, May 1972, Gene Daniels; Sulfur dusting of grape vines, May 1972, Gene Daniels; Burning Discarded Automobile Batteries, 1973, Marc St. Gil; Jar of undrinkable water from well near coal mine, 1973, Eric Calonius

The preponderance of these images showed environmental degradation, boosting people’s recognition of the need for regulations and enforcement.

Requiring industries to take responsibility for cleaning up the messes they made was imperative for dealing with environmental issues, since one factory or mine or project could cause tremendous damage. Enforcement was needed so that industries would invest the money and effort needed to address the problems they were creating.

The responsibility of the individual was also part of the equation. As one history of the EPA says, "Environmentalists versed in ecology had recognized that when it came to pollution, humans were often victims and villains simultaneously. In the case of urban smog, many of those who complained about the health and aesthetic effects of air pollution commuted to work in the very automobiles largely responsible for the problem."

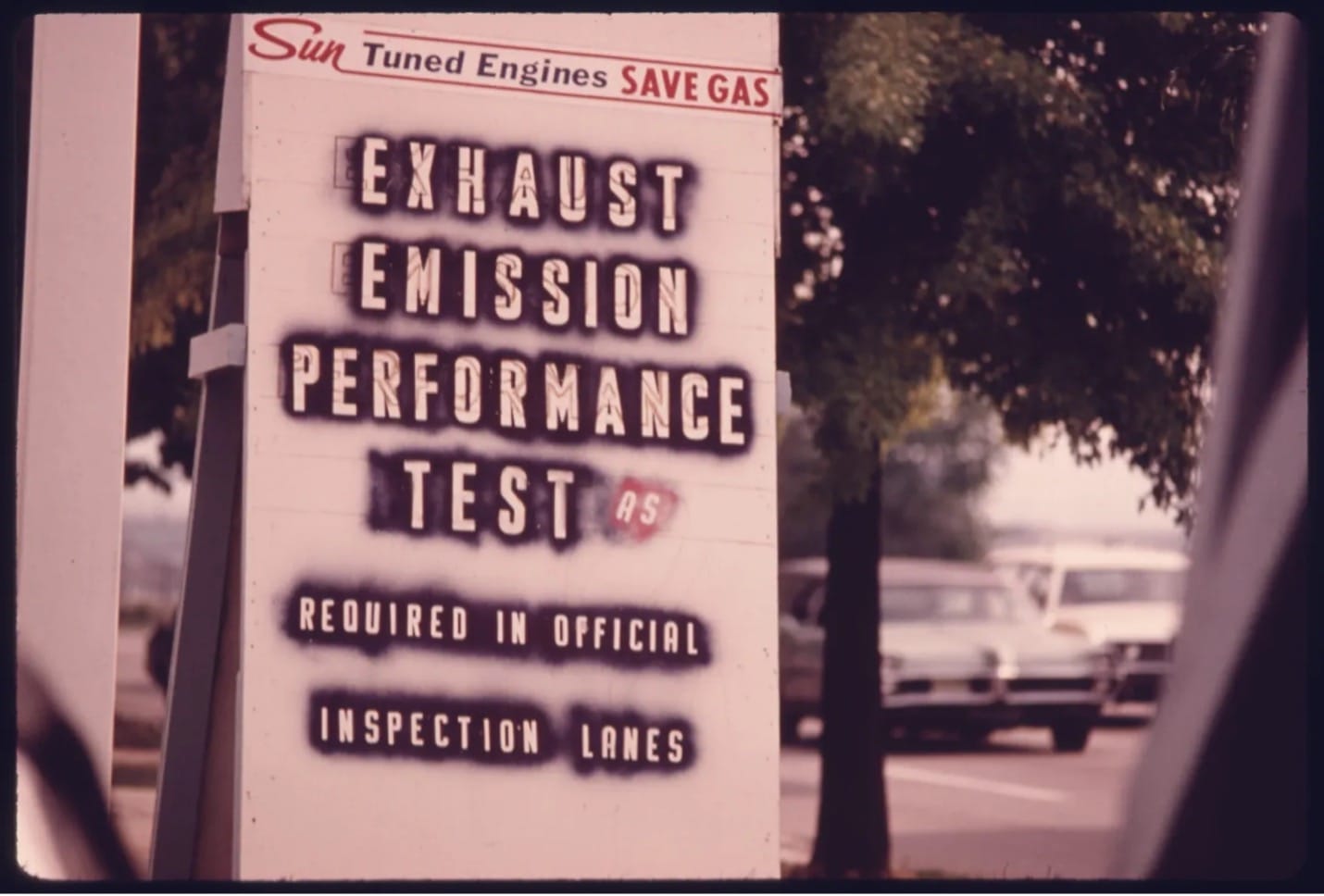

Experimental housing near Taos, New Mexico, David Hiser, 1974; Closeup of a Sign to Pass Emission and Safety Tests, 1975, Lyntha Scott Eiler; Cleaning Up the Roadside in Onset, 1973, Ernst Halberstadt

Documerica certainly wasn't the core work of the EPA, but it was a strategic way to show how necessary that core work of research, documentation, regulation, and enforcement was in the effort to have a healthy environment.

Since its founding, it has been expected that the EPA would expand and address new threats to the environment as they became known. Thus, climate change, one of the most dire modern threats to the environment, logically came under the EPA’s purview, and its recent removal from the EPA’s website is very worrisome.

In addition, the work being done by the EPA in areas of environmental justice has prioritized communities most overburdened by pollution (such as areas in Appalachia), where community members often do not have the money or power to fight for their right to clean water, air, and soil. With the current DEI pullbacks, much of this work has been put on hold or cancelled.

I am struck by the aptness of this verse from Ezekiel:

Ezekiel 34: 18 - Is it not enough for you to feed on the good pasture? Must you also trample the rest of your pasture with your feet? Is it not enough for you to drink clear water? Must you also muddy the rest with your feet?

Perhaps we need an updated Documerica project—one that shows current crises such as plastic pollution, damage to the land done by fracking and drilling, and the intensification of wildfire, flooding, and storms due to climate change. Or perhaps this is not even enough. With it becoming more and more apparent that one country’s actions affect places beyond their borders, perhaps we need a Docuworld instead.

Feel free to leave a comment below (you can sign in through your email) or contact me directly at louise.conner@circlewood.online.

Louise

A final call! If you would like to respond to the invitation in my last post to send in a photo you had taken of something "outside your door," do so by Friday and I will include what you send within the wonderful collection I have already received from readers.